The party balloon in the cupboard under my stairs was blown up on Super Saturday during the London Olympics. It’s now 489 days old, and counting…

The party balloon in the cupboard under my stairs was blown up on Super Saturday during the London Olympics. It’s now 489 days old, and counting…

We threw a party on super Saturday – well it was just Saturday 4th August 2012 until all the GB golds started rolling in. A friend brought round some red, white and blue balloons left over from a Jubilee celebration, so we blew them up. The day after the party, there was one red, one white and one blue balloon left. In celebratory mood, I left them there to brighten up the room. They’ll go down in a few days, I thought.

They didn’t.

A couple of weeks later, I thought I’d get them out of the way by putting them in the cupboard under the stairs. (No, I’m not sure why either!) They’ll go down in a few days, I thought.

They didn’t.

Several months later, I found the blue balloon looking deflated where the hoover had been leaning against it. The others will go down soon, I thought.

They didn’t.

Both the red one and the white still look, well, they still look like party balloons, some 489 days later.

Most of the balloons bit the dust during the party. One was popped by a surprised toddler, who promptly burst into tears, and then plucked up the courage to pop another. Many of them took a battering as we punched them in the air on Mo Farah’s 5000m victory. But, surprisingly, three survived for many months, and, even more surprisingly, two of those are still going 489 days later….

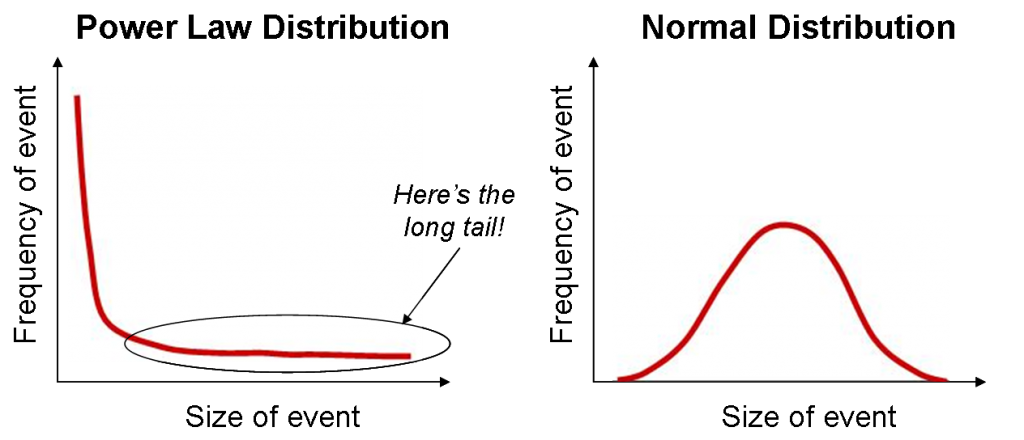

What does this tell us? It tells us about long tails and power laws. You might not have heard of these terms, but power law distributions with long tails are common in nature. Basically they tell us that some events are common (e.g. a lot of party balloons have a very short life span – they pop at a party) and some happen more rarely (e.g. a couple of party balloons are still looking like balloons over 15 months later). Most importantly, they show us that unexpected things (‘extreme events’) DO happen. And they’re not as rare or unexpected as you might think.

So, what does a story about a balloon in the cupboard under the stairs and long tails means for leaders at all levels in organisations?

- NOTICE – let’s notice the surprising and unexpected

You could never have predicted that I’d still have two party balloons in the cupboard under my stairs 489 days after the party. But if you notice the odd, surprising and unexpected, then you can ask questions about it. If you just think – well that’s unlikely to happen again – you’ll miss that opportunity. This is particularly important during organisational change (and, let’s face it, that’s most of the time for many of us these days). The reason it’s particularly important during change is because the odd, surprising, or unexpected event or behaviour – even if it seems very small – may offer a weak signal about new organisational patterns that are beginning to emerge.

- EXPLORE – let’s explore the enabling conditions

Why are these balloons still here after 489 days? Is it something about the balloons? Is it something about the conditions in the cupboard under my stairs? Is it something about the way they were inflated? Is it something about my unexpected reluctance to pop them? (Nope, I’m not balloon phobic).

In organisations, when we notice something surprising or unexpected, a possible weak signal about a new pattern, it’s helpful to explore that with others, to benefit from different perspectives. We can ask questions about the enabling conditions and what made that event or behaviour possible. Is there a new pattern emerging? Are existing behaviour patterns being amplified in some way?

- RESPOND – let’s learn from it and choose how we respond

So, in the unlikely event that I wanted to preserve a balloon in the future, I might put it in the cupboard under my stairs, where it’s protected from extremes of heat and cold and is away from the light. But perhaps the conditions in the cupboard under the stairs might also be good for storing other things – such as apples or potatoes.

As leaders, if we notice unexpected and surprising events, and explore them with others, we might discover some interesting patterns which could herald new opportunities. If we do so, we can choose how we play into those emerging patterns. And, then we can learn from those experiments in live change by continuing the cycle of noticing, exploring and responding.